This year marks 175 years since ‘Black 47’, the worst year of the devastating ‘Great Famine’ in Ireland. James McCabe reviews this tragic event and analyses its causes and lasting impact on Irish history.

Every place is unique in its own way, but Ireland is one of the only parts of the world that has fewer people today than it did 175 years ago. In 1845, it had a population of over 8.2 million. Seven years later, more than one million people had died of starvation or disease. By 1870, another three million had left the island.1 Songs, books and films have been made about the Irish Famine, but no words or images can truly capture the scale of devastation wrought by this catastrophe.

The provinces of Connacht and Munster on Ireland’s west coast were hit particularly badly. These lands were populated by millions of rural labourers and poor farmers. Most were illiterate, and many spoke only Gaeilge (Irish). They lived in small settlements or villages, but not villages as we think of them today. There were no pubs or shops. They were usually just groups of kin-related farming people living in clusters of one-room mud cabins. These people had a rich oral culture of folk customs, singing, storytelling, music and dance. Visitors who wrote about their travels through the West of Ireland on the eve of the Famine would often describe the exceptionally noisy nature of these settlements. There was a lot of chatting, talking and singing in these communities; whereas nowadays the West of Ireland conjures an image of a quiet and remote place.2

At the risk of painting a sentimental or romanticised picture of these people as universally kind, ever-singing, two-dimensional characters; it’s worth emphasising that they were just living, breathing people, with the same human frailties and contradictions as us. What was distinctive about them was that they depended for the most part on a single source of food: the potato. Across the whole of Ireland, four out of ten people ate no solid food except potatoes, and many more were heavily dependent on them.3 When the blight arrived in Ireland in 1845 it wiped out a third of the potato crop. In 1846 the entire crop failed.4

Not a natural disaster

However, the resulting famine was not just a natural disaster or the result of food scarcity.

Not every stratum of Irish society was impacted equally. Karl Marx observed, “The Irish famine… killed more than 1,000,000 people, but it killed poor devils only.” It is absolutely the case that the poorest people in Irish society were hit the hardest. Yes, they were victims of Phytophthora infestans, the microorganism that wiped out the potato crop, but they were just as much the victims of the exploitation and oppression of the capitalist system.

To truly understand the causes of the Famine, an investigation into the social conditions of Ireland and its colonial relationship with Britain is indispensable. Some of the major factors of this relationship included:

1) British capitalism’s exploitation of Ireland’s population and natural resources;

2) The British ruling class seeing land clearances of the rural poor as a necessary step to shift agriculture in Ireland from crop harvesting to cattle rearing;

3) To achieve the above aims, it was necessary to promote a subordinate Irish capitalist class that was focused primarily on agricultural production and not industrial production across most of the island.

These three processes all began long before the onset of the potato blight but were ramped up during the Famine years. The British ruling class used the crisis as an opportunity to further consolidate its domination of Ireland and clear the land of the rural poor in the name of “modernisation”.

Eyewitness to desolation

Friedrich Engels, the close collaborator of Marx, visited the West of Ireland in 1856. Only four years after the Famine had ended, he described his experiences:

“Ireland may be regarded as the earliest English colony and… is still governed in the same way; here one cannot fail to notice that the English citizen’s so-called freedom is based on the oppression of the colonies… How often have the Irish set out to achieve something and each time been crushed, politically and industrially! In no other country have I seen so many armed police… The countryside is strewn with these derelict farmhouses, most of which have only been abandoned since 1846. I had never imagined that famine could be so tangibly real. Whole villages deserted; in between the splendid parks of the smaller landlords, virtually the only people still living here. Famine, emigration, and clearances between them have brought this about… the countryside is a complete wilderness unwanted by anybody.”5

As Engels documents, a certain class of people had been virtually wiped out, while the wealthy remained. He also places the responsibility for the destitution he witnessed at the feet of the British ruling class.

England’s oldest colony

It is widely known that colonised countries served as sources of raw materials for the capitalists of the dominant coloniser countries, but those raw materials were also processed into commodities which were then shipped back to the colonies to be sold. This led to an unequal relationship in which the capitalists of the coloniser countries grew stronger while also preventing any industrial competitors from developing in the colonial countries.

Marx wrote a lot about Britain’s colonial relationship with both Ireland and India. He once characterised the latter as the “Ireland of the East”, highlighting how Ireland and India had a similar relationship to Britain despite the massive differences between the two countries.6 Some of the colonial policies that he documented were:

a) The destruction of the local industry of the colonised country;

b) The creation of local markets in the colonies for commodities manufactured in Britain;

c) Land clearances of small farmers and rural labourers to develop capitalist agriculture;

d) Enormous internal migration, or emigration, of the poor farmers and labourers who were cleared from the countryside to act as a cheap source of labour in the cities;

e) The suppression of political rights within the colonised country by the ruling class of the coloniser or oppressor country.

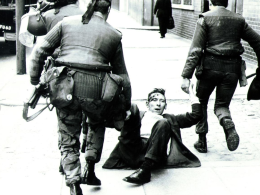

Colonial rule rested on a military occupation. While the British constitution forbade a standing army on home territory, the landscape of Ireland was littered with British army garrisons and patrols. The number of police officers per head in Ireland far exceeded those of England, Scotland and Wales — a blatant symbol of the country’s national oppression.7

Britain’s breadbasket

The colonial occupation of Ireland was consolidated by the British ruling class between the 1500s and 1600s. However, this was not a smooth process and there were many struggles of resistance in that period.

A major armed revolt known as the 1798 Rebellion had hundreds of thousands of supporters, but it failed in its aim of ending British rule in Ireland. In response, the British ruling class unleashed a wave of violent repression. The Irish parliament in Dublin was dissolved and direct rule from London began. This culminated in the Act of Union of 1801 which subsumed Ireland completely into the United Kingdom. Trade policies prevented a domestic manufacturing industry from developing in Ireland. The country was transformed it into an agricultural appendage of British capitalism. Karl Marx noted that the aim was to make Ireland “an agricultural district of England, marked off by a wide channel from the country to which it yields corn, wool, cattle, industrial and military recruits.”8

Ireland’s role as the “breadbasket of Britain” was visible in its landscape. Practically all the major towns and cities were seaports from which vast quantities of food were shipped to feed British cities. In 1819, an official Select Committee report in London recommended establishing an efficient transportation network in Ireland to “‘insure to England supplies of grain at moderate prices, which might render it [England] wholly independent of foreign countries for food of its manufacturing population”.9 Essentially, a major factor in the industrialisation of Britain was the active underdevelopment of most of Ireland, India and other colonies. The advanced capitalist countries of the world developed at the expense of the colonial countries.

Class composition of 19th century Ireland

Ninety-five per cent of Ireland’s landmass belonged to a small group of mainly Protestant landowners; approximately five thousand families. Most of these landowners were descendants of English colonists from the wars of conquest of the 1500s and 1600s.

The land was worked by tenant farmers who sublet land to smaller farmers. Millions of these small farmers, known as cottiers, worked without cash payment in return for the right to occupy a small piece of land on which to subsist. Millions of rural labourers also worked for big landlords and tenant farmers in return for a very small, rough strip of land. The bigger tillage farms in the eastern part of Ireland that produced wheat, barley and oats, relied on the labour of seasonal migrants from the West known as spailpíní. Large numbers of spailpíní also worked in the fields of Scotland and England in certain seasons. Any meagre wages received from this seasonal work were mainly used to pay rents to landlords or tenant farmers.

Many of the big landowners were absentee landlords who lived lavish lifestyles in Britain. Overall, this class was averse to investing its capital into modernising farming methods and conditions on its land through fencing, draining, constructing farm buildings and so on. Capital was used to pay taxes to the British government.10

Draconian regime

The free-market doctrine of the British establishment in the 1840s was steeped in anti-working class and anti-poor prejudice. The theory held that the state should not provide any sort of social safety net and the most destitute had to jump through hoops to get any relief. A system of workhouses had been well established throughout Britain and Ireland before the onset of the Famine. To prove that they were penniless, a person seeking food relief had to enter the workhouse where they were forced to do hours of intense work such as breaking stones or crushing bones to produce fertiliser. To add insult to injury, families were separated from each other upon entry.

The workhouses in Ireland had been built to house a maximum of 100,000 people. But due to the social crisis caused by the Famine, they housed over 900,000 by 1849. Diseases such as typhus spread like wildfire in these cramped conditions and the death rate soared. In the workhouses, the poor died amongst strangers whereas on the outside, children watched their parents die and parents watched their children die. It was horrific. The elderly and the very young were particularly vulnerable. The child population actually halved in Connacht and most of Munster by 1851.11

The workhouses were utterly overstretched. The government’s answer to this? They launched major public works schemes in which men could toil building walls, roads and harbours for extremely meagre wages. By March 1847, over 700,000 people worked on these infrastructure projects, but a lot of the schemes served no useful purpose. The projects are often described as having built “roads to nowhere and walls around nothing”. Many who worked on the projects died from exhaustion or exposure to harsh weather conditions. The government eventually introduced soup kitchens in the summer of 1847. No labour was required in exchange for the soup. This caused the mortality rate to drop. Unfortunately, the scheme was abandoned in October 1847, and the deaths began to mount again. Conditions for the poorest sections of the population worsened dramatically in the later years of the Famine. There are well-documented cases of survival cannibalism in 1847, 1848, and 1849. There is no evidence of a person killing another to eat their corpse, however; the cases involved people trying to survive by eating the flesh of those who had died before them.12

Resistance

What can’t be omitted from a study of the Famine is that the oppressed and exploited fought back against the conditions they faced. The work of Socialist Party member, Dominic Haugh, has shed light on the struggles of working people in Limerick City who organised to stop food from being exported during the Famine. In October 1846, “the plunder of provisions in the city took on an organised and systematic fashion, with a network existing in the working-class tenements to distribute the plundered food… Those plundering cartloads of supplies resorted to shooting the horses to prevent the drivers from galloping off. The frequency of shooting incidents increased, and relief scheme workers regularly supported the plunder of provisions by forming a cordon to stop police and troops who were trying to prevent the food supplies being carried off.”13

So, the public works schemes actually became a vehicle for labouring people to coordinate civil disobedience: “Protests against the export of provisions were almost always planned and plotted by the labourers on the public works schemes.”14

Land clearances

Overall, the British government spent £8 million on relief measures in Ireland in the Famine years. This was a paltry amount when you consider that £14 million was spent on the military and police occupation of the island over the same period.15 The number of troops increased significantly to meet the needs of landlords and bigger farmers. Between the years 1849 to 1854, a quarter of a million people were evicted from their homes, usually under the watchful eyes of the police or military.16 Beyond the evictions, anyone who sought relief had to leave their home and surrender it to their landlord.

The government wholeheartedly welcomed the evictions of rural labourers and cottiers. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston spelt this out very clearly to the cabinet on 31 March 1848 (it should be borne in mind that Lord Palmerston was an absentee landlord himself, who was evicting his own tenants en masse in County Sligo): “It is useless to disguise the truth that any great improvement in the social system in Ireland must be founded upon an extensive change in the present state of agrarian occupation, and that this change necessarily implies a long-continued and systematic ejectment of Smallholders and of Squatting Cottiers”.17

The decimation of the lives, the language and unique culture of a whole group of people was seen as a necessary price to pay for agricultural modernisation; what Marx called “the clearing of the estate of Ireland.”18 The Economist magazine, a mouthpiece for British capitalism, gave a clinical celebration of this process: “The departure of the redundant part of the population of Ireland… is an indispensable preliminary kind of improvement… The revenue of Ireland has not suffered in any degree from the famine of 1846-47, or from the emigration that has since taken place.”19

Why no embargo on food exports?

Historians of the Famine correctly lay a heavy emphasis on the fact that people need not have starved given that there was a surplus of food produced in the country. An argument is often made that the British government should have enacted an embargo on food exports to keep food in the country. They chose not to do this to avoid disrupting British trade, but also to avoid opposition from larger Irish tenant farmers.

What too often gets overlooked in Irish nationalist narratives around the Famine is that British troops were very often used to protect convoys of grain and cattle owned by Catholic Irish farmers. This produce was destined for export. And these farmers were not a small section of the population. Cormac O’Gráda argues that “The export of corn belonged not to the landless or near landless classes, but Ireland’s half a million farmers, who certainly would have resisted the lowering of prices that an export embargo would have brought in its train.”20

Origin of the Irish Catholic bourgeoisie

Most historians of the Famine agree that there was deep anti-Irish racism embedded in the British establishment in the 19th century. The view that the Irish, and particularly Catholic Irish were inherently inferior to British people had roots stretching back hundreds of years. This took a particularly heinous form with the discrimination contained in the Penal Law system of the eighteenth century. The Penal Law system elevated the Anglican Church, so Presbyterians were subjected to a second-class status. Catholics were forced into a third-class status.21 Restrictions were placed on Catholics learning to read and write; owning guns; serving on juries; entering certain trades and professions and they couldn’t vote in elections. There were laws against intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics; and Catholics were not allowed to buy land from Protestants at a time when most of the land was owned by wealthy Protestants. By the mid-18th century, only 5% of Ireland’s land was owned by Catholics, even though the vast majority of the island’s population was Catholic.22

This policy of divide and rule was cultivated by the ruling class of Britain as a method of maintaining social control. They believed that by institutionalising sectarian divisions, they could prevent struggles from below emerging. Ultimately, their core aim was to maintain a colonial relationship with the population of Ireland and its natural resources. Nevertheless, the 1798 Rebellion threatened both the system of religious segregation and British rule. The organisation that led this uprising, the United Irishmen and its leadership was mainly made up of Presbyterians who wanted an end to systemic discrimination. In anticipation of growing political discontent in Ireland, some of the most discriminatory aspects of the Penal Laws had been lifted in the 1780s and 1790s.

The British ruling class then dramatically changed tack and saw merit in the idea of cultivating a subordinate Catholic bourgeoisie that could see its interests aligned with the status quo. The British state even began to provide state funding to the Catholic Church, while the Catholic hierarchy roundly condemned the 1798 Rebellion. A centralised professional police force was established in Ireland in 1822 and consciously recruited to their ranks with a degree of religious impartiality. By the 1850s, 70% of this force were Irish Catholics. Therefore, you generally had local cops enforcing the evictions of people known to them in rural areas during the Famine. By this time, 61% of school teachers and 50% of civil servants were also from a Catholic background. These layers and the Catholic merchants in the cities were often related to the wealthy farmers and mill owners who profited from food exports to Britain.

Rise of the cattle ranchers

Before the Famine, there had been a significant shift from the production of grain on Irish farms to the raising of cattle for export. When Britain was at war with most of Europe and the US in the early 1800s it needed Ireland to produce wheat. By the 1840s, it had access to a plentiful supply of cheap grain from the US and Russia. Engels noted, dryly: “Today England needs grain quickly and dependably—Ireland is just perfect for wheat-growing. Tomorrow England needs meat—Ireland is only fit for cattle pastures. The existence of five million Irish is in itself a smack in the eye to all the laws of political economy, they have to get out but whereto is their worry!”23

This change accelerated significantly during the Famine years. Cattle farms were able to expand onto the land that had previously been occupied by cottiers and rural labourers, and in a parallel process, employment in agriculture was progressively reduced. There was no need to employ many labourers on grassland that was only used for cattle grazing. James Connolly observed that “as long as cattle raising pays better than raising men and women it will flourish in Ireland as elsewhere.”24 Hugh Dorian, a 19th-century teacher from a Catholic poor-farmer background in Donegal, described the consolidation of land by the bigger pastoral farmers after the Famine: “the miserly narrow-living class of people, those who were little thought of before, crept up in the world and became possessors of land such as was never in the tribe or family before… some did undermine and injure their poorer neighbours and got property without paying a farthing.”25

In 1923, a Labour Party senator stated that “the ranches were created by filling the emigrant ship.”26 Many cattle ranchers had made the transition from tenant farmers to owner-occupiers of their land by the time the country was partitioned into two sectarian states, North and South. In the South, the state operated to serve the interests of the southern big-farmer class and its live exports to Britain. All the while, the bulk of the working population suffered through mass unemployment, poverty and emigration.

Aftermath and legacy of the Famine

While Europe and the US saw rapid urbanisation in the late 1800s, Ireland had lost many of its small and medium-sized towns. With the exception of Belfast, there was a loss of population and industry for many decades. Due to the expansion of the linen and ship-building industries in Belfast after the Famine, a certain myth developed that the northeast was largely unaffected by the devastation of the Famine. In fact, of the four provinces, Ulster had the third-highest death toll during the Famine years. And the mainly Presbyterian city of Belfast had a particular concentration of deaths from disease and hunger. Its workhouse was filled far beyond capacity and many textile workers had been thrown out of work in 1847 as the Famine coincided with a Europe-wide credit crisis and industrial downswing.27

Two towns that saw growth in the second half of the 19th century were Cobh and Dun Laoghaire. Both specialised in the business of exporting Irish people to the cities of the Anglophone world. By 1890, an incredible 39% of those alive who had been born in Ireland were now living overseas.28 Most emigrants worked as day labourers; building bridges, railroads and working in the factories of Britain and the US. Many would play a pivotal role in the fight for trade union and socialist change in these countries. Two giants of the Irish labour movement, James Connolly and Jim Larkin, were born in Edinburgh and Liverpool respectively to Irish parents.

Many aspects of the Famine can be deeply disturbing to read and think about. Unfortunately, some of the most barbaric aspects of this event are alive and well today. An unprecedented amount of wealth and technological development sits alongside increasing levels of deprivation, violence and hunger. The central problem today is the same as it was during the nineteenth century; it’s not a question of the amount of wealth that exists, but a question of who owns and controls the wealth? The inevitable mass movements of the coming years should be armed with a programme for socialist change; where the resources of society are owned and controlled by the majority rather than a tiny elite. In the words of James Connolly: “The day has passed for patching up the capitalist system; it must go!”

Notes

1. R.F. Foster, 1988, Modern Ireland: 1600-1972, p.345

2. The Hunger: The Story of the Irish Famine, RTE documentary (2020)

3. Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, p.286

4. “The Great Irish Famine”, In Our Time: History Podcast (2019)

5. “Letter from Engels to Marx”, May 1856, Marx-Engels Correspondence, www.hiaw.org

6. Thomas C. Patterson, 2009, Karl Marx, Anthropologist, p.132

7. Theodore Allen, 2012, The Invention of the White Race, Volume 1: Racial Oppression and Social Control, p.112

8. Karl Marx, Capital: Volume One, www.marxists.org

9. David Nally , 2012, “The colonial dimensions of the Great Irish Famine”, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845-52, p.66

10. T.A. Jackson,1976, Ireland Her Own: An Outline History of the Irish Struggle, p.205

11. William J. Smyth, 2012, “‘Variations in vulnerability’ understanding where and why the people died”, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845-52, p.195

12. “The Great Irish Famine” In Our Time: History Podcast (2019)

13. Dominic Haugh, 2019, Limerick Soviet 1919: The Revolt of the Bottom Dog, p.39 l 14 Ibid, 39 l 15 The Hunger, RTE (2020)

16. David J. Butler, 2012, “The landed classes during the Great Famine” in Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845-52,p. 265

17. David Nally, 2012, p.73

18. Karl Marx, 1867, ‘Outline of a report on the Irish Question to the Communist Educational Association of German Workers in London’, www.marxists.org

19. Kevin B. Anderson, 2016, Marx at the Margins: on Nationalism, Ethnicity, and non-Western Societies, p.119

20. Cormac O’Gráda, 2000, Black ‘47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in History, Economy and Memory, p.125

21. Ruth Coppinger et al, 1998, Revolution in Ireland: 1798, p.5

22. R.F. Foster, 1988, p.206

23. John Bellamy Foster, “The Rift of Éire” Monthly Review, www.monthlyreview.org

24. James Connolly, 1909, ‘Capitalism and the Irish Small Farmers’, The Harp, www.marxists.org

25. Hugh Dorian, 2000, The Outer Edge of Ulster: A Memoir of Social Life in Nineteenth-Century Donegal, p.228

26. Conor McCabe, 2014, Sins of the Father: The Decisions that Shaped the Irish Economy, p.68

27. Christine Kinealy and Gerard Mac Atasney, 2012, “The Great Hunger in Belfast”, Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845-52, p.434

28. R.F. Foster, 1988, p.345