By Kevin Henry

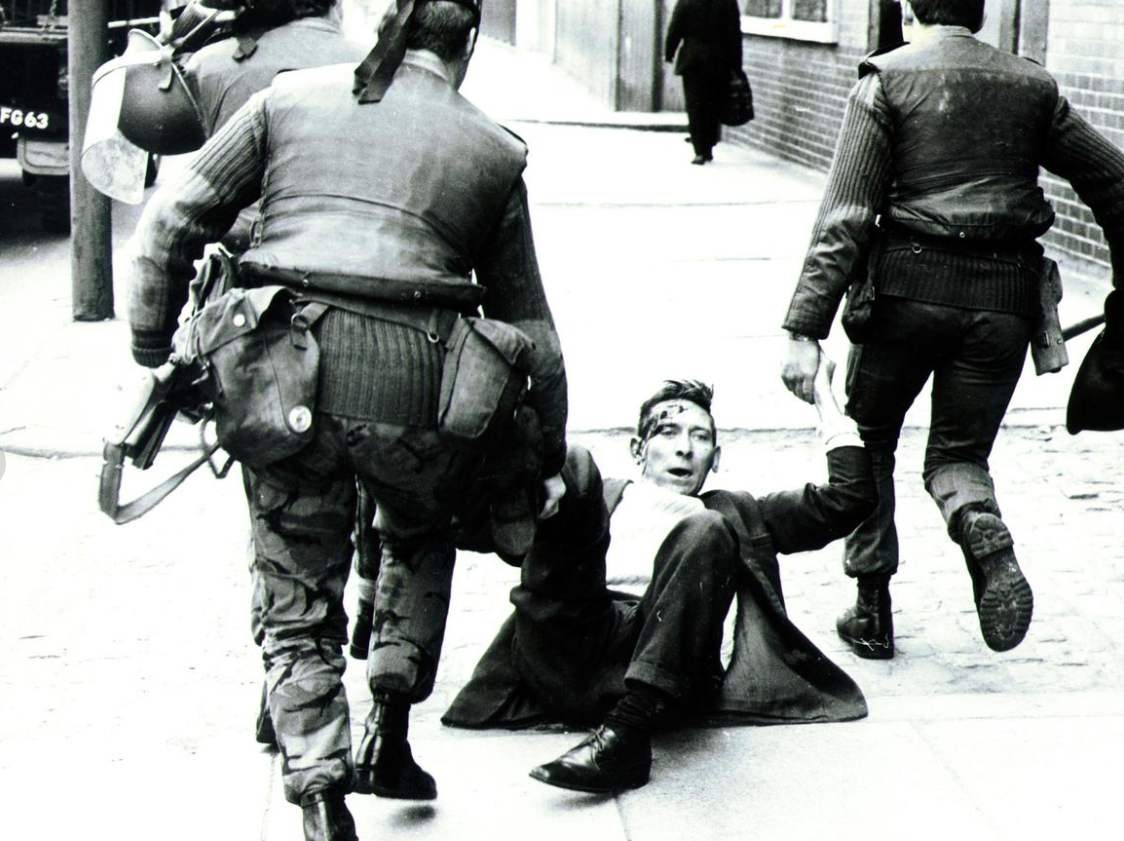

This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of Operation Demetrius and the start of internment without trial, introduced by the reactionary Unionist government at Stormont and the British state. This brutal repressive action saw hundreds of innocent, working-class people rounded up across Northern Ireland by the British army and jailed in a matter of days.

The ability to intern was introduced initially as an amendment to the Special Powers Act of 1922, when the new Northern state was handed repressive powers by the British government. It had been introduced on previous occasions but this was its most widespread use, lasting until December 1975. During that time, 1,981 people were interned. The move inspired the apartheid South African Minister for Justice, John Vorster, to proclaim that he “would be willing to exchange all the legislation of that sort for one clause of the Northern Ireland Special Powers Act”.

Operation Demetrius

Operation Demetrius was the biggest British military operation since the Suez Canal crisis. In Ballymurphy alone, there were 2,000 members of the hated Parachute regiment. In what would be known as the Ballymurphy massacre, ten innocent civilians were killed at their hands. For years, the truth of what happened to these victims was hidden, and the British Army spread lies that they were IRA volunteers. Only in recent weeks, following an independent inquest, has a Prime Minister apologised for the actions of the state in Ballymurphy. But now the British government wishes to whitewash the troubles by granting an amnesty for Troubles-related offences.

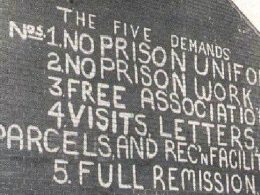

Many internees were tortured. During Operation Demetrius, 14 men – subsequently dubbed the ‘hooded men’ – were chosen for ‘special treatment’ and were taken to a secret interrogation centre. The men were thrown to the ground from low-flying helicopters while hooded. They were subject to the ‘five techniques’ – being hooded, held in stress positions, subjected to ‘white noise’, and deprived of sleep, food and water. These methods would later be used across the world – including by the US military, the Israeli state and the military junta in Brazil – on the premise that they were legally considered ‘enhanced integration techniques’, rather than torture. The remaining ‘hooded men’ are still fighting for justice and to end the use of these torture techniques, perfected in Northern Ireland, across the globe.

Overwhelmingly, this policy was directed against the Catholic population on the pretext of fighting the IRA. The British state and Unionist establishment had been contemplating the introduction of internment for some time, but the supposed justification was the killing of three off-duty Scottish fusiliers by the IRA. This provoked a significant backlash in Britain and among Protestants in the North, reflected in thousands of shipyard workers protesting for internment after these shootings.

‘Internment a class issue’

Rather than weakening the IRA, internment strengthened the organisation. Many of the Catholic working-class areas most affected erupted into mass protests, and many young people joined the IRA in response to the repression. The year that followed was the most violent of the Troubles. Sectarian division was massively reinforced, with thousands of both Catholics and Protestants leaving their homes and moving out of areas where they were in a minority.

At the time, Militant – the predecessor of the Socialist Party – argued that, “Internment is not a religious but a class issue”, and that while “today it is the Catholics who present the problem (for the state – ed). Tomorrow it may be members of the Protestant nuisance groups and the day after that it will be members of the Labour Movement.”

Indeed, partly because of bad intelligence, only a minority of the 342 initially ‘lifted’ were directly associated with the IRA. Of those, many were of the old IRA generation, veterans of the 1950s ‘border campaign’ and no longer active. The majority were political activists, including a number of prominent figures in the civil rights struggle. Fifteen members of the left-wing organisation Peoples Democracy – including its leading figure, Michael Farrell – were interned. Some were active trade unionists, including those who had played a prominent role in local areas during a recent postal strike.

Mass resistance, but workers’ movement fails to take the lead

In Catholic areas, the protest movement led to a rent and rates strike which would later famously be betrayed by the SDLP. There was no doubting the mood of mass opposition that existed, but it was based only in one community. The majority of Protestants remained either neutral or supportive of internment as a way to hit back against the IRA’s campaign, which they saw as an attempt to bomb and shoot them into a state where they would become the oppressed minority. So long as it could rely on the indifference or support of a majority of the population, the state could sustain its policy, albeit with difficulty and at the cost of significant turmoil and political breakdown.

Militant argued that the trade union and labour movement couldn’t ignore this issue, that it was the only force that could build united opposition to internment across the sectarian divide by explaining it was ultimately a class issue. This would not have been easy or straightforward, but the alternative of ignoring the issue and leaving it in the hands of various sectarian forces proved much worse. This had been an important battleground between the left and the right-wing inside the workers’ movement. The trade union leaders did issue a statement of opposition to internment but refused to take the issue to the members. Instead, they organised a meeting with Unionist Prime Minister Brian Faulkner, afterwards saying they were ‘pleased’ to get a commitment that such measures were temporary.

For the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP), the situation was much worse. In the public eye, the NILP shared responsibility for internment, since their senior spokesman – David Bleakley – sat in the cabinet which introduced it. This was despite the fact that he committed at the party conference to resign if internment was introduced. He only resigned weeks later, under pressure from a section of the NILP membership. At the same time, the leadership issued a statement threatening branches that publicly commented on the question of internment. Only the Young Socialists, including Militant members, defied the party officials and issued a leaflet at the mass rallies opposing internment. Overnight, many strong branches of the NILP in Catholic areas, such as Derry and West Belfast saw mass resignations. This was a further nail in the coffin of the NILP as a major force with support in both communities.

Lessons for today

The lack of leadership from the workers’ movement allowed a generation of young people to be drawn into the dead-end of paramilitarism. Internment was only one attempt by the British state to deal with their problems in Northern Ireland through repression. Later, they moved on to a policy of criminalisation which led to horrific conditions in the prisons and sparked the 1981 hunger strike, which will be the subject of a further article. As Militant and now the Socialist Party has consistently explained, these are class issues.

Socialists have a responsibility to address issues of state repression, including ‘anti-terror’ legislation initially directed against forces with whom we have little in common, as these laws can later be turned against the left and working-class movement. Opposition to repression must include standing against attempts to use Covid as a cover to attack the legitimate right to protest, as we have seen locally around BLM rallies, protests against gender violence and on picket lines.

In Northern Ireland, failure by the left and workers’ movement to address these issues allows sectarian forces to shape the discussion around them. Today, we need to learn from the lessons of the past and build a socialist alternative that can unite workers and young people across the sectarian divide around their common interests, including in opposition to state repression.