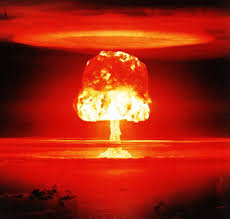

The North Korean bomb test on 3 September, the most powerful yet, and the bellicose reaction of the US, underlines the volatile and dangerous situation in the peninsula and entire region.

The huge blast in the north of the country was felt in South Korea and China. The regime claimed it was a hydrogen bomb, up to fourteen times more powerful than the last bomb test.

Hours later, South Korea, with US backing, held military exercises and missile launches in a simulated attack on North Korea.

Amidst the cranking up of war rhetoric on both sides, further missile tests by North Korea are expected over the next days.

Many people in the region and across the world are understandably fearful that the aggressive actions of the US and North Korea’s arms programme can lead to armed conflict, by design or ‘accident’, and even nuclear war. The thought of an armed exchange that would affect the whole planet – a ‘nuclear winter’ – costing untold lives and environmental destruction, rightly horrifies millions.

Appalling as North Korea’s weapon programme is, it is nothing compared to the 7,000 nuclear warheads the US superpower possesses. And the US is the only country to have ever used nuclear weapons, on the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, in 1945, killing hundreds of thousands.

While Trump condemns North Korea’s threat to “world peace”, it is the US imperialist superpower that has unleashed over 6,000 bombs in several countries, so far, in 2017, killing thousands of innocent poor civilians.

The Trump administration gave a chilling response to the North Korea bomb test. When asked, “Will you attack North Korea?” Trump replied, “We’ll see”.

US Defence Secretary James (“Mad Dog”) Mattis, warned North Korea faced, “a massive military response” to any threats to the US or its allies, which would see North Korea’s “total annihilation”. At the same time, reflecting the very limited options facing the White House and its contradictory positions, Mattis stated that the US has no plans for “regime change”.

Sanctions

The US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, declared that Kim Jong-un was “begging for war” and called for an end of all economic links with North Korea. New sanctions being discussed (US sanctions against North Korea were first put in place in 1950) include ending all oil supplies, stopping the export of North Korea workers (it is estimated that more than 50,000 North Koreans work in China and Russia, sending back foreign currency to Pyongyang) and all financial transactions.

This is a direct threat to China’s interests, which is the main trader with North Korea and its primary oil supplier.

North Korea is already subject to recent UN sanctions, including a ban on coal, lead and seafood exports, worth $1bn a year or a third of annual revenues.

In a tweet, Trump threatened “stopping all trade with any country doing business with North Korea”. This suicidal policy would mean ending trade between the US and China, the world’s two largest economies, triggering major trade wars and plunging the global economy into chaos and most likely severe depression.

The Chinese regime called North Korea’s latest nuclear test an “error” and pointedly called for the crisis to be resolved “peacefully”.

China and Russia’s ‘freeze for freeze’ proposals – the US and South Korea to stop massive military exercises on North Korea’s borders in return for Pyongyang stopping nuclear and missile testing and for talks – is dismissed out of hand by the White House.

Both China and Russia border North Korea and are vying with the US in the Eurasia region. They criticise Pyongyang’s nuclear arms programme partly because it gives US imperialism the pretext to vastly increase its military power on the Korean peninsula.

At the same time, China and Russia steadfastly oppose severe sanctions, including oil embargoes, as they could lead to social chaos in North Korea or even the collapse of the Pyongyang regime, with millions of refugees entering China and even Russia. They fear the end of the North Korea ‘buffer’ would see a US dominated ‘reunified’ Korea, with weapons of mass destruction on their doorsteps pointed towards them. It is likely that China and Russia will seek to significantly water-down sanction proposals brought by the US and its allies to the UN.

In an angry response to the sanctions threat, Russian president Putin argued that Kim Jung-Un is not “mad”, as the western media often describe the North Korean dictator, but that he is acting rationally. “Everyone remembers well what happened with Iraq and with Saddam Hussein. Hussein gave up the production of weapons of mass destruction . . . And they also know and remember that well in North Korea,” Mr Putin said. “And you think that North Korea will abandon [its course] because of some sanctions?”

Indeed the regime of Kim Jong-un appears to have speeded up its nuclear arms programme to act as a ‘deterrent’ against a US-led attack. Gaddafi, the Libyan dictator, gave up his nuclear programme in 2003 in return for pledges of economic integration and security deals with the west. But the US and its allies supported rebels against Gaddafi, in 2011, which led to the downfall of his regime and Gaddafi‘s grisly end.

Whatever sanctions might be brought to bear on North Korea – for which working people will suffer the most – the Pyongyang regime regards nuclear weapons as its only real bargaining chip and chance to survive.

Stalinism

The North Korea regime’s bomb and missile testing certainly compounds the risk of conflict but the main culprit for creating this dangerous situation in north east Asia lies with the aggressive, reckless Trump administration.

The North Korea regime is a particularly grotesque form of Stalinism but its development has been strongly influenced by the decades-long military threat from US imperialism.

Japanese imperialism brutally annexed Korea in 1910 and in the 1930’s the Korean independence movement turned to armed resistance. Kim Jong-un’s grandfather, Kim Il-sung, led a 13 year struggle that ended with Japan relinquishing control of Korea in 1945.

As WW2 drew to a close the US feared that Soviet soldiers, who were entering the northern part of the peninsula, along with tens of thousands of Korean guerrilla fighters under the leadership of the Korean Communist Party, would take all Korea under control. American State Department planners chose the 38th parallel to divide Korea and 25,000 US troops entered southern Korea to establish a brutal military government.

After a series of south Korean incursions into the north, full scale war broke out on 25 June 1950. The US military commander, General McArthur, advocated dropping 20 or 30 nuclear bombs on the north (for this indiscretion, he was relieved of his command by US President Eisenhower). Under the banner of the UN (including 60,000 British troops) the conventional bombardment of the North, previously the most industrialised region of Korea, caused enormous casualties (including two million civilian deaths) and massive destruction of the country’s infrastructure.

At the same time, the southern military regime carried out vicious repression against anyone associated on the left. It is estimated that at least 300,000 people were detained or executed or ‘disappeared’ in the south in the first few months of the war. Many of those responsible served the Japanese rulers and were put back in power by the Americans.

The Korean War ended in 1953 with the border where it started, without a formal peace treaty and with the US refusing to recognise the ‘Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’.

The war and decades of US military threat resulted in North Korea becoming an increasingly isolated, monolithic form of Stalinism. Kim Jong-un is a hereditary leader of a regime notorious for its xenophobia, cult of personality and bogus ‘Juche’ (self-sufficiency) ideology. The totalitarian regime holds hundreds of thousands of political prisoners in labour camps.

Reactionary South Korea regimes and the continued military threat gave the Stalinist regime room to justify its rule. The US, with ‘operational control’ of the Korean army, stood by as two right wing military coups took place in South Korea, in 1961 and 1980.

In the first few decades of its existence, North Korea, on the basis of a planned economy, was also able to outpace the south economically, significantly raise living standards and literacy, health and education rates. It became a largely urbanised, industrialised country.

However, like all Stalinist states, top-down, bureaucratic rule undermined the achievements of the planned economy and became a fundamental barrier to its further development. The military apparatus, with around a million troops and a massive array of conventional weaponry, is a massive burden on the economy.

North Korea economy

The economy was hit very hard by the collapse of the Soviet Union after 1990, which deprived North Korea of cheap imports. This was compounded by flooding in 1995-96 that led to famine.

The Kim Jong-il leadership was forced to allow the growth of private farmers’ markets, and in 2002 the regime announced the development of two Special Economic Zones.

Both formal and informal markets have grown, as well as private enterprise. In 2013, Kim Jong-Un announced his “byungjin line”, a policy of simultaneous development of the economy and nuclear weapons. This has seen permits for 400 markets. As well as this, unofficial markets now account for between 70 and 90 per cent of total household income. The South Korean central bank stated last month that the North’s economy grew in 2016 by 3.9%, the fastest pace in 17 years. However, the economy is “far from recovering to pre-crisis economic performance,” according to Professor Byung-Yeon Kim at Seoul National University.

Capitalists throughout East Asia are keen, of course, to exploit North Korea’s cheap labour.

Only genuine workers’ democratic control and management, at all levels of society in North Korea, could see the full potential of the planned economy realised. This entails overthrowing the despotic Kim Jung-un regime and linking up with the working class of South Korea in their struggle against capitalism and imperialism.

While Trump rants against North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, it was the US that introduced nuclear arms into the Korean peninsula, in 1958, until they were pulled out following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since 1991, the US has carried out regular flights of nuclear capable bombers in South Korean airspace and US submarines that can carry nuclear arms frequently sail in surrounding waters. The US also maintains a massive ‘conventional’ military presence in South Korea.

Nuclear capability

In response, North Korea embarked on the long road to nuclear capability and tested its first medium-range missile in 1992 and its first long range rocket in 1998. It used the threat of nuclear weapons and its huge conventional arsenal to force the US super power into negotiations. The regime needed economic concessions to avoid collapse and sought an end to the strategic siege imposed by the US since the end of the Korean War.

US president Bill Clinton admitted that “we actually drew up plans to attack North Korea and to destroy their reactors, and we told them we would attack unless they ended their nuclear programme”. But the bald facts staring US imperialism – war on the peninsula would claim up to one million dead, including up to 100,000 Americans, and cost trillions – saw a swerve in US policy and a negotiated ‘agreed framework’ with North Korea.

Under the deal, North Korea would suspend its nuclear weapons programme, the US would provide economic assistance in the form of oil, food and the construction of two (non-plutonium-producing) ’light water’ reactors for electricity generation, and the US would move towards “full normalisation of political and economic relations”.

The deal produced an eight year freeze (1994-2002) on all the North’s plutonium facilities and went some way towards phasing out its missiles. The US, however, never fulfilled its promises, leading North Korea to secretly renew its nuclear weapons policies.

A big section of the capitalist class in the Southern Korea, however, were strongly in favour of reaching agreement with the North, to prevent its collapse and a mass refugees crisis. This resulted in a summit meeting between North and South regimes in June 2000.

But the hawkish George W Bush administration ditched the Agreed Framework and broke off talks with North Korea. In his infamous 2002 State of the Union Speech, Bush declared North Korea to be part of an “axis of evil”.

Nevertheless ‘Six-Party Talks’ began in 2003 between North and South Korea, the US, Russia, China and Japan. North Korea would be given economic assistance in return for an undertaking not to pursue nuclear weapons. In July 2007 the International Atomic Energy Agency confirmed that the Yongbyon plutonium-producing reactor and fuel assembly plant was shut down.

However mutual suspicion and distrust between North Korea and the US proved unbridgeable; North Korea was angered by unending demands for information about its nuclear programme and the US claimed North Korea had continued a secret uranium enrichment programme.

Under the Obama administration, despite the toning down of war rhetoric, there was no major change in policy towards North Korea. The coming to office of the aggressive, reckless Trump administration has seen, once again, a dangerous ratcheting up of tensions.

US imperialism’s limited options

Yet Trump faces the same limited options as previous US presidents, even more-so now that North Korea appears to be on the brink of possessing nuclear armed missiles (which Pyongyang claims will reach the American mainland).

Shortly before he was fired by the White House, Steve Bannon, the ‘alt-right’ former advisor to Trump, described US and North Korea relations as a proxy for US “economic war” with China. There is “no military solution” for stopping North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes, Bannon blurted.

“Forget it,” he told American Prospect magazine (16 August). “Until somebody solves the part of the equation that shows me that ten million people in Seoul don’t die in the first 30 minutes from conventional weapons, I don’t know what you’re talking about, there’s no military solution here, they got us.”

With massive artillery lined up on the border between the North and South, it is estimated by military analysts that 100,000 people in Seoul could die in the first few days of conflict. And there is no guarantee a US military strike could destroy all the hidden parts of North Korea’s nuclear programmes.

Bannon’s view is shared by many US officials and former officials. “He’s absolutely right,” said former North Korea nuclear negotiator Joel S. Wit. “This [a US first strike] is not a credible threat, and it really hasn’t been since the 1990s. We’ve been pretending it’s credible, but it really isn’t.”

In an editorial (5 September), the Financial Times bluntly stated, “The world has no choice but to live with a nuclear-armed North Korea. The US…cannot change this fact without taking catastrophic risks.”

In August, South Korean President Moon Jae-in made similar comments: “I can confidently say there will not be a war again on the Korean Peninsula.”

After the 3 September North Korean bomb test, Trump accused South Korea of “appeasement” and raised doubts about continuing a US-South Korea free-trade agreement – a highly provocative statement that the White House soon backed away from.

Moon Jae-in faces domestic pressure having come to office after huge protests forced the impeachment of his right wing predecessor. He pledged to repeal repressive security laws, to foster reconciliation with North Korea and that Seoul will adopt a more independent foreign policy the US. While Moon Jae-in is under intense pressure to agree to take more US missiles, it is reported that his government is considering developing its own nuclear arms programme.

Volatile and dangerous

Despite the overwhelming facts militating against a US first strike, the situation remains volatile and dangerous, involving two unpredictable leaders, Kim Jong-Un and Donald Trump. The New York Times warns that Trump needs to starts talks with Kim Jung-Un, “before design or miscalculation leads to war”.

Misjudged ‘tactical’ military actions and skirmishes or ‘accidental’ incidents can spiral into wider, devastating conflict.

The White House sends out contradictory statements on how it intends to deal with North Korea. This reflects not only the unstable character of the Trump presidency but the intense debates and divisions taking place within US ruling circles.

Sections of the US establishment counsel more aggressive action. In a gung-ho editorial, the Wall Street Journal called for the deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea and encouraged North Korea “elites to defect or stage an internal coup”. It went on to callously call for mass starvation to be used a weapon against Pyongyang: “withholding food aid to bring down a government would normally be unethical, but North Korea is an exceptional case”. (WSJ, 5 September 2017)

Armed conflict on the Korean peninsula would provoke huge anti-war and anti-imperialist protests across the world, even revolutionary movements – not least in the US where the Trump administration is already deeply loathed by big parts of the American population.

Protests took place this week in South Korea against the instalment of new US missiles. The South Korean working class has a proud record of mass struggles against militarisation, and mass movements overthrew previous military dictatorships.

In the long run, the US will most likely have to face the prospect of entering negotiations with North Korea and reaching some sort of deal to try to “contain” nuclear-armed North Korea. The Washington Post reports that the United States and North Korea have maintained “a quiet diplomatic channel over the past months that could be used to set up more substantial negotiations”.

However the only way to ensure long term peace and stability in the region is for the development of strong international working class opposition to the aggression of the Trump administration, against militarisation of the Korean peninsula and for the scrapping of all nuclear arms worldwide.

Linked to this, is the struggle to fundamentally change society – run for people’s needs not profits – by the working class across the Korean peninsula, the region and the US. The unification of Korea on a genuine socialist basis, and the creation of a voluntary and equal socialist federation in the region, would see an end to class exploitation and wars.