By Donal Devlin

Twenty-five years ago this month, Palestinians living under military occupation rose in mass revolt against the Israeli State. This was the ‘Second Intifada’ – intifada being the Arabic word that roughly translates into “uprising” or “shaking off”.

This was the second time in a generation that Palestinians, facing Israeli subjugation, revolted. The First Intifada began in December 1987, after 20 years of living under occupation and military rule. The mass of the population of Gaza and the occupied West Bank engaged in a mass movement that shook Israeli rule to its foundations. It was a grassroots movement, democratically organised and co-ordinated from below.

First Intifada betrayed

The First Intifada was tragically betrayed by the leadership of the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organisation) and its main faction, Fatah, led by Yasser Arafat, with the signing of the Oslo Accords in September 1993. The Palestinian writer Edward Said aptly referred to it as the “Palestinian Versailles”.

The agreement de facto meant the continuation of the occupation of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza under a different guise through the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA). The PA had a very limited self-government over a fraction of the West Bank and Gaza – the key population areas – and was run by a corrupt, collaborationist regime led by Arafat, later to be succeeded by Mahmoud Abbas, who still rules today. The Israeli State was able to outsource its daily repression of the Palestinian populace to the subservient PA, whose armed forces were trained by the CIA.

Numerous negotiations in the 1990s and early 2000s appeared to offer a vague promise of a Palestinian State, based on the June 1967 lines, ie a mere 21% of historic Palestine. At the same time, Palestinians would have to relinquish the historic right of return of refugees and their descendants expelled during the Nakba in 1947-1948. The apartheid regime that Palestinians lived under within the Green Line (the Israeli State’s internationally recognised borders) would also remain.

Occupation continues

This promise of Palestinian statehood proved to be a cruel joke. Israel’s Zionist ruling class, backed by its patron US imperialism, was never willing to countenance the existence of such a state; at most, it was only willing to see the existence of a Palestinian equivalent of the “bantustans” or “black homelands” that existed in apartheid South Africa. This would be a truncated, semi-state that Israel would dominate militarily and ensure it remained economically impoverished and underdeveloped.

In the years following the signing of the Oslo Accords, successive Israeli governments created facts on the ground that increasingly made the viability of such a state even less workable. There was a massive expansion of the number of heavily armed and subsidised Israeli settlers, and settlements that further seized Palestinian land and resources.

On 28 September 2000, after years of dashed hopes, seething anger at Israeli occupation exploded in revolt. The catalyst was a cynically provocative march led by then Israeli Defence Minister Ariel Sharon (who was elected Prime Minister the following year) to the site of the Dome of the Rock, the third holiest site in Islam, located in East Jerusalem. Sharon was a war criminal who, among other things, was the architect of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which culminated in the massacres of the Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps.

The uprising was not confined to the occupied Palestinian territories; significantly, it spread to towns and villages beyond the Green Line – as Palestinian citizens of the Israeli State fought back against decades of systemic discrimination and dispossession. Much of North Africa and the Middle East was rocked by mass protests in solidarity with Palestine.

Murderous repression

Predictably, the Israeli Occupying Forces’ (IOF) response to the Intifada was one of murderous repression. In the first days of the Intifada alone, they fired a total of 1.3 million bullets at unarmed Palestinian protesters. Two days after the uprising began, footage was taken of Jamal al-Durrah trying to protect his 12-year-old son, Muhammad, as they desperately sheltered from Israeli fire in Gaza City. Muhammed was mortally hit and succumbed to his wounds days later. The footage of this atrocity went global, epitomising the brutality of the Israeli State.

After months of protests, clashes and further Israeli atrocities, with 20 Palestinians killed for every one Israeli, in March 2001, almost inevitably, the first in a new campaign of suicide bombings targeting Israeli Jewish civilians took place. Initially, amongst Palestinians, there was understandable sympathy towards the suicide attacks, given that often very young people were willing to sacrifice their lives in acts of resistance against relentless and vicious Israeli oppression. No doubt these acts were motivated by a sense of desperation and a justified desire to strike a retaliatory blow against the might of Israel. However, they were also horrific and were destined to be a dead-end strategy for the struggle for Palestinian liberation.

Indeed, their counterproductive nature became increasingly apparent to those Palestinians living under occupation. By the end of the Second Intifada in 2005, polls showed a majority were opposed to these bombings. Moreover, as Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi has pointed out, the Israeli regime saw these bombings as strengthening, not weakening, its hand. It is no coincidence that one of the most prominent Hamas leaders assassinated in 2003, Ismail Abu Shanab, was one of the most vocal opponents of these attacks.

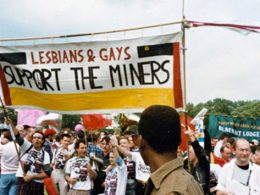

A key lesson from this revolt is the vital necessity of international solidarity action with Palestinians, from working people in the region and globally, to link up with a democratic mass movement of Palestinians from below, as the most effective way to take on the might of Israel – one of the most militarised powers in the world. A quarter of a century on, the struggle of the Palestinian people has never been more urgent, and the need for a revolutionary socialist change in the region never greater.