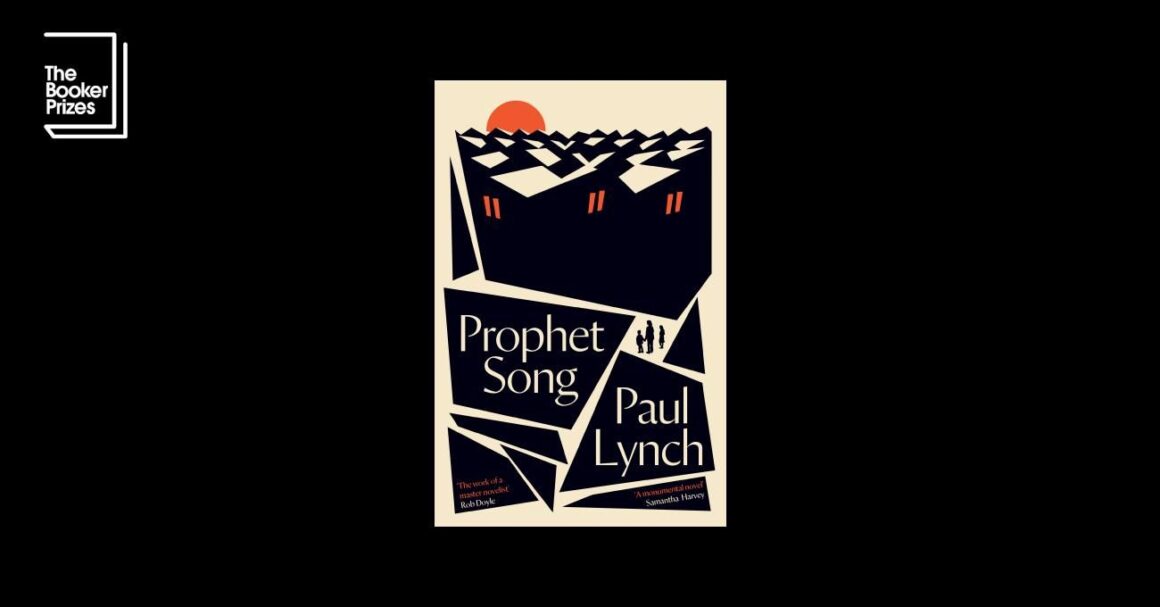

Prophet Song

By Paul Lynch

Oneworld Publications, 2023

Reviewed by Finn McKenna

“This place is going to become a hellmouth all over again, the regime is about to agree to let the UN open a humanitarian corridor from Lansdowne Road stadium through the port tunnel to the north, you’ll be allowed to leave like rats so long as the piper calls the tune”

Paul Lynch’s novel Prophet Song was shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize. Written in a world that had gone through the election of Trump and Bolsonaro, and seen a rise of conspiracy theorists and far-right agitators with the Covid pandemic, while also clearly influenced by modern conflicts such as the decade-long civil war in Syria, the book is clearly one that rushed out of Lynch’s imagination. Its lack of paragraphs epitomising the urgency of the writing; the form is captivating and there’s no denying Lynch is a wordsmith.

Undoubtedly, Lynch gave serious consideration to the development of far-right and reactionary forces as he approached sketching this tale, which is centred around the life of Eileen Stack – the wife of a trade union leader who has been interned in the Curragh by a far-right regime that has been in power for several years.

The setting of the book is unclear – it’s in Dublin, but it may be an imagined parallel unfolding of reality, or it may take place in the not-so-distant future. The question of time is one that preoccupies the writer, as again and again his narration muses upon the condition of temporality; the blip in the moment of existence and history in which this story occurs:

“This low and motionless sky, the windows with their blinds drawn, the street in silent witness as the people live out their lives, the cycles of births and deaths, the endless recurrence of human generation, a hundred years goes by.”

The weight of the passage of time speaks to the heaviness of life that one suffering within a far-right dictatorship would experience. Eileen Stack’s life and sense of everything is completely dislocated with the arrest of her husband. The author’s conscientiousness is unquestionable; his focus on the life of a woman struggling to contend with the pressures of everyday life – work and family-rearing – while trying to cope with the disappearance of her husband reflects how seriously Lynch is attempting to grapple with the condition of daily life, of ordinary people, crushed under a dictatorship.

As mentioned already, the focus of the story is on the Stack family. The revelations about Ireland’s descent into a far-right regime is told through the prism of how life is experienced by Eileen. In this way, clues are revealed to the reader about the metamorphoses of changes within Irish society. Still existing is An Garda Síochana, the civil service departments, the judiciary etc. In this way, Lynch demonstrates the familiarity of this tale with our present status quo.

But the story also envisages new appendages of the police to target those who are proclaimed to be enemies of the state by the government, and how all institutions of power have been dominated by the ruling-party. Eileen Stack sees members and adherents of the far-right ruling-party in her everyday life; in Dublin City’s streets, in the supermarket, and at work. A pillar of strength contained in the story is Lynch’s ability to present how such a transition in Ireland is imaginable.

There are, however, pitfalls in the story that stood out. It’s clear that Lynch researched far-right movements historically. The fact that Larry Stack is a persecuted trade union leader speaks to an understanding of far-right forces seeing the organised workers’ movement as their main enemy.

The lack of reference to existing political forces, be they the parties of Irish capitalism or left and socialist forces, throughout the book is something that raised an eyebrow though. As the book develops, an overt civil war between the state power and “rebels” deepens. There is no allusion to the political make-up of such rebels. In that sense, there is something of an ahistoricism to the story, as its omission of existing and historical political groups, paramilitary forces and parties feels like a missed opportunity.

Perhaps this was a decision consciously made by Lynch, and in fairness this is a work of fiction rather than a political treatise. With that said, the air of unreality persists when there’s discussion throughout the book of people escaping the grips of the regime by heading up north. The idea that a fascist government would be in power in the south of Ireland without a similar (or more extreme) regime existing in Britain feels somewhat unbelievable, as political upheaval in one country absolutely impacts the other.

Whatever the book fails to deliver in terms of continuity from history to the modern day, it compensates in the graphic detail of the strife and trials of life under such a regime. The book finishes in a way that Lynch should be proud of, as it presents to the reader the imagined situation of Irish people becoming refugees – something that is of the utmost importance in today’s world, with refugees scapegoated more and more by the far right. What Lynch demonstrates in his tale is how war and fascism turn ordinary civilians into refugees fleeing for their lives, and provokes reflection on how such a societal nose-dive could happen to ordinary, everyday people in our own time.

Leon Trotsky once observed;“If there are prophets and poets who can be said to have been ‘ahead of their time’, it is because they have expressed certain demands of social evolution not quite as slowly as the rest of their kind.” Although Prophet Song isn’t directly dealing with historical necessity, it is sounding the alarm as to what could come to pass if we fail to challenge the danger posed by the far right.