Laura Fitzgerald explores the evolution of the socialist feminist work of the Socialist Party and the international organisation to which we belong, including assessing the roots of an ignominious split away by a minority in a leadership position in 2019, on account of its opposition to the Irish section’s role in ROSA – Socialist Feminist Movement.

The Socialist Party took a turn towards radicalising left-leaning, feminist youth in the early 2010s, as well as a growing abortion rights movement, including through our leading female and LGBTQ members initiating ‘ROSA – Socialist Feminist Movement’ on International Women’s Day, 2013. Rather than consciously rejecting weak spots in our tradition, our approach emanated from applying ourselves to a concrete development and utilising every tool available to us: looking again at theoretical contributions on Marxism and gender oppression; drawing lessons from previous feminist waves; developing out a strategy to build the movement that could win abortion rights; consciously seeking to build the socialist feminist wing of the growing pro-choice movement in order to cohere both a working-class, struggle-based feminism in opposition to liberal feminism, and also to draw around us those radical youth and working-class women and LGBTQ people from which we could build the forces of revolutionary socialism.

In hindsight, this was a changed approach in our tradition – a necessary one. The Socialist Party in Ireland and its forerunner, Militant, have a history of taking principled stances in opposing all forms of discrimination, and taking initiatives such as inviting gay rights speakers to Labour Youth summer camps in the 1980s that were attended by many hundreds; standing up to anti-choice groups like SPUC, and being part of abortion rights protests, all at a time when it was ‘unpopular’ to do so. However this work was mostly reactive, piecemeal and not sufficently rooted in a socialist feminist perspective. This is evident in a review of decades of Militant and Socialist Party Conference documents, rife with frequent omissions in relation to socialist feminism – a deficiency evident in our late decision to positively embrace the term itself, done at a Socialist Party Conference in the early 2010s.

In 2018, a major dispute broke out in the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI), with the central leading body, the International Secretariat (IS) launching an attack on the Irish section, the Socialist Party, on account of its socialist feminist work, in spite of, and perhaps because of, the success of the ROSA’s intervention into the abortion rights movement. A major internal dispute enveloped the CWI, with a minority who remained loyal to the IS splitting away in 2019, with the majority renaming the organisation as International Socialist Alternative (ISA).

The IS and the executive of the England and Wales section had much crossover. Throughout the CWI, there was never a uniform approach on socialist feminism, with some sections having a decades-long proud tradition of knitting it into all aspects of its work. This review will make reference in detail to the England and Wales section of the CWI – both because of its importance in the Trotskyist movement, but also because its political approach was reflected inside the IS across the decades. In a shameful example of its current trajectory, the minority around Peter Taaffe and Hannah Sell that split away – the “refounded” CWI – is open to coalescing with the increasingly transphobic George Galloway.1

The roots of the very worst attitudes displayed at the height of the bitter dispute that enveloped the International in 2018 – namely a thinly-veiled, myopic and conservative suspicion of feminist struggle at the heart of the IS – can be traced back over decades. The congenital deficiencies in the CWI related to a Marxist approach to women’s oppression have expressed themselves in our theory, perspectives and practical work in different ways over our history.

During the 2018-2019 dispute, the ex-members wrote that there was a “grain of truth” in the ‘post-feminist’ idea that “women were on the verge of winning equality… in many countries”. This proposition, as well as being imbued with crass insensitivity to the prevalence of gender-based violence in every country in the world which has been a vital driver of the feminist wave that has emerged since the 2010s, seems to at least be pointing away from the idea that gender-based oppression and capitalism are so intertwined that the latter has to be dispensed with to begin to end the former.

In departing in some way from the foundational point that capitalism is utterly incapable of ending gender-based oppression, or using formulations that implied being anything less than crystal clear on this question, did represent a departure from our tradition on behalf of the IS Majority. Rather than representing some qualitative change in their position, however, this departure was a product of the lack of a systematic, integrated and serious approach to our socialist feminist work over decades.

Lacklustre theoretical approach on gender- and sexuality-based oppression

Women’s oppression is part and parcel of capitalism. Hence feminist movements and struggle have been a feature of capitalism throughout its history. The development of capitalism heralded opportunities for women to organise in struggle, as well as developing new ways in which women’s and LGBTQ oppression would manifest itself and be reproduced. In contrast to feminist ideas or concepts, Hal Draper located the first examples of women organising for feminist demands as taking place in tandem with the French Revolution’s “upswing from 1789-1793, and above all in its left wing.”2 A crucial part of the liberatory potential for women contained in the onset of capitalism was tied to that of the working class as a whole. It was precisely the creation of the working class, a social force with the power to be capitalism’s ‘gravedigger’, which allowed for the possibility of socialist change and the elimination of the material basis for all exploitation and oppression.

In our history and tradition in the CWI, the contribution of Engels has been correctly highlighted. In a taboo-busting and extraordinarily enlightened contribution for its time, Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State made a number of contentions that generally hold up, including backed up by more accurate anthropological research and findings that have become available since Engels’ time.3 The central thesis: that gender-based oppression didn’t always exist and therefore was not immutable and could be ended, was and remains vital. Citing the beginning of class-divided societies linked to developments in agriculture circa 10,000 years ago as the ‘world-historic defeat of the female sex’, Engels’ claimed that the ‘primitive communism’ of early hunter-gatherer societies show that the model of the patriarchal family, including monogamous marriage (with the emphasis being with the woman’s monogamy), was not the natural way of things but was a socially-imposed means to pass on private property through a male line.

Understanding the connection between the beginning of gender- and sexuality-based oppression and class-divided societies means understanding that a society without classes – where the economy is socially owned and democratically planned – could be one without oppression; making the socialist struggle inextricably linked to the struggle for women’s and LGBTQ freedom and vice versa. This is a key foundation of a Marxist analysis of gender-based oppression and formed the central plank of the analysis of the CWI throughout its history.

However, even on this question, there was a lack of deeper engagement. For example, Marx’s notebooks from later in his life, which were not published until after Stalin’s death, writings that were the subject of many debates and discussions on the left regarding socialist feminism, were not really considered or delved into in the CWI tradition. This work from Marx illustrated a heightened sensitivity to different questions of oppression, to their importance as an impetus for class struggle, and how important it was for socialists to take the right approach in order to be able to build a united class struggle. These writings also gave an insight into the ongoing discussions, collaboration and fine-tuning of political analysis and positions of Engels and Marx over decades – as opposed to there being some ‘final word’ in one text on women’s oppression.4 Engels himself did a number of revisions of the Origin text as more information became available to him – one could not credibly argue that the spirit of this was the tradition embodied in our theoretical work on women’s oppression throughout the CWI.

The work of Clara Zetkin, who pioneered a working-class and socialist feminist approach via her work on the left-wing of the SPD in Germany, was not sufficiently highlighted in the CWI’s tradition. Similarly, the work of female revolutionary leaders in seeking to establish an International Communist Women’s Conference and elected leadership as part of the work of the Communist International, as well as the work of the Zhenotdel after the Russian Revolution, which sought to wage a struggle to further women’s emancipation in every respect, were not sufficiently discussed or considered a central basis to our work.

The indisputable fact that women played a vital role in the Russian Revolution itself – tens of thousands of women workers were the first to rise up during the February Revolution – was a huge boost to the female cadre in the Marxist movement who were pushing for a revolutionary, working-class feminism. The Stalinist counter-revolution consciously sought to attack the gains made in the revolution, disorganising and demoralising the working-class women’s movement. Trotsky details this in the chapter, “Family, Youth and Culture” in The Revolution Betrayed precisely because socialist feminism was as integral to the revolution as the attack on it was to the counter-revolution.5

Lack of theoretical struggle

While Engels’ contribution was of course brilliant and foundational, there were naturally many gaps that a number of academic Marxists have sought to fill. If central to women’s oppression is the role of the traditional family and the passing of private property through a male line, what does this mean for the working-class masses who are ‘property-less’? If capitalism inherited women’s oppression from previous incarnations of class-divided societies, how has it been reproduced and ingrained in different ways throughout capitalism’s history? It was to the detriment of the CWI that we did not sufficiently engage in this theoretical struggle ourselves, as evidenced in weaknesses in our perspectives related to women’s oppression and feminist struggle over the decades, but most clearly seen in insufficient attention to the special impact of neoliberalism on working-class and poor women – something that is part of the material basis for the new feminist wave of the 2010s and beyond.

Some trends within the school of social reproduction theory (SRT) have made useful insights in relation to these questions. Those around the Feminism for the 99% pamphlet have played a role in popularising some basic left feminism – namely the need for a conscious split from and opposition to bourgeois, establishment feminism – and this has been informed by strands of SRT.6

The most pertinent idea behind SRT is that the oppression of women under capitalism is connected to the particular role that women, especially working-class and poor women, play in reproducing the labour force for capitalism. This reproduction of the workforce for capitalism is done via unpaid labour of poor and working-class women, especially in the domestic sphere, and also by elements of the capitalist state where women predominate as workers, such as schools and hospitals. By honing in on the particular role that women play as underpaid care workers and as unpaid carers under capitalism (something rooted in the ideology of the patriarchal family), which is vital to maintaining and reproducing capitalism’s labour force from which surplus value is extracted, they succinctly and clearly sum up an inextricable connection between exploitation and oppression in capitalism. While you can find formulations that are in line with this insight in CWI material including from the 1990s, it mostly lacked the same precision.

Second wave feminism barely a footnote

If you scour the material of the CWI historically on women, there are a number of facts that present themselves, as well as some political themes. Firstly, it’s the lack of material that is striking. Gender oppression is absent from the founding documents of the CWI, written in 1970, an important year of the second feminist wave. The main theoretical journal of Militant, the Militant International Review, had only one theoretical article on women’s oppression between 1969 and March / April 1994. The final issue in 1995 contained the only article on gay rights. Given that feminist mass struggles of the second wave, as well as the gay liberation movement, were contemporaneous to this material, the absence of comment and analysis of the same is telling.

If one goes back to the roots and early days of the CWI, particularly when one looks at the material of Ted Grant and the attitudes that lie behind this material, clear problems present themselves. This includes a dismissive attitude to struggles against oppression outside the labour movement. Unfortunately it also includes a suspicion of gay rights activism and even an implication that this is a petit bourgeois concern. Echoes of such crude economism and a patronising attitude to struggles against oppression is something that has persisted in the IMT (founded by Ted Grant and Alan Woods after the split in 1992) organisation over the decades.

Another feature you will find in early CWI material is a somewhat patronising and contradictory attitude in relation to working-class women. It’s usually contended that they are a more backward section of the working class, which is capable in times of revolution of great sacrifice and radicalism, but whose role is perhaps questionable at other times.

The origins of the CWI were based on a necessary break with forces within the Trotskyist Left that had developed a wrong, disorientating perspective in the post-war period. Within the USFI, a position developed that at root placed a major question mark over the revolutionary potential of vital sections of the working class within the advanced capitalist countries, and in doing so, over revolutionary working class leadership and potential full stop. In this way, the USFI leadership not only looked to, but often ‘tail-ended’ student, feminist and anti-colonial movements to try to fill the gap. In orientating to important social struggles, it failed to raise the revolutionary socialist programme, key to which is the need to link up with the organised working class, and the working class as a whole to build the social weight and power to make revolutionary change.

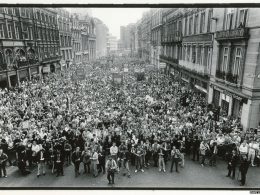

This approach had very serious real-life consequences for the socialist struggle. Notably, the organisation was ill-prepared for the working-class revolutionary general strike in May 1968 in France and failed to make the impact it could have in a revolutionary situation in a huge industrialised capitalist country in a year of revolution. The CWI’s necessary foundations in rejecting this approach and perspective, however, failed to contain a readjusted Marxist perspective on questions of oppression – one that was inextricably intertwined in the whole programme and perspective for working class consciousness, agency and power. This then tended to mean that the CWI’s approach to anti-oppression struggles was characterised too much by what it was (correctly) rejecting, and not enough based on a developed and proactive Marxist analysis and perspective towards the same. This particularly pertained to issues of feminism and LGBTQ liberation.

LGBTQ rights – corrected position but without sufficient review

Ted Grant’s appalling position on gay rights, while never the official position of the organisation, was later rejected in Militant and the Socialist Party, but this was done in a haphazard fashion. LGBTQ members were vital agents in pushing this. Helen Redwood, who was a founding member of the LGBT caucus in Britain and went on to become the national LGBT organiser, said about the same that, “whilst we should be critical of the poverty of our earlier analysis and neglect of work on LGBT+ issues that left us trailing behind other organisations on the left, once LGBT comrades ‘took the bull by the horns’, in general, there was no block to the caucus developing this aspect of work. Nevertheless, how much more effective could our intervention have been into the exploding movements of LGBT+ people in the 1980s and 90s had this aspect of work been led from the top and integrated into our national perspectives and strategy.”

Peter Taaffe did reference in a limited way some mistakes regarding the LGBTQ struggle in the past in an article in Socialism Today, and also in a defensive way in the Marxism in Today’s World pamphlet. But this was not sufficient. Recognising mistakes should be done in a more systematic and political fashion in which the organisation is enabled and empowered to fully draw out lessons, or mistakes will be repeated.

While the IS frequently referenced Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) – an inspiring display of solidarity from the defining class battle that was the 1984-5 British miners strike – but they never owned up to an uncomfortable reality, namely that one founding member of LGSM was in Militant and has stated that “I’d been in the Militant for 10 years – though they didn’t support or even acknowledge LGSM and had a very dismissive attitude on gay rights.”7

Some of the economistic and dismissive attitudes referenced above are found in material well into the 1980s. For example in 1985 Ted Grant wrote in an internal bulletin: “The American SWP exaggerates support for liberal middle class issues… ‘as women’s liberation’ and ‘gay liberation’. It is of course correct to fight against any persecution of homosexuals and to work for equal rights for women. But it is necessary to fight for working class women’s struggles and to concentrate on the working class issues as the main work of Marxists…”8 How callous when you consider the historical context, namely the heartwrenching discrimination and suffering that the gay community was being subjected to during the AIDS epidemic.

Politically, it utterly separates out economic questions, “the working class issues”, from questions of oppression. It ridiculously implies that issues of oppression, sexual repression etc. are middle-class concerns. It fails to understand that the intersection of exploitation and oppression can be especially radicalising. Implicit is the idea of a defensive position on these issues – that we oppose repression / oppression, but that we don’t concern ourselves with proactive calls for increased freedom and liberation for the oppressed. This can be directly contrasted with a Bolshevik approach to fighting oppression that’s exemplified in Lenin’s What Is To Be Done (1902). In raising class consciousness, Lenin advocates for all socialist worker activists to be ‘tribunes of the people’ who speak up against all forms of injustice that the system metes out no matter what class is affected, in an effort to truly agitate against the system and build working-class agency, consciousness and power.

The notion that working-class women are a more backward section of the working class is evident in the 1985 British perspectives document that states that, “conditions of life under capitalism are the cause of the political backwardness of women… They try to find a road out of the problems of life under capitalism by building their own little nests, separate and apart from the struggle of the working class. But as soon as they come to realise the impossibility of opting out of the struggle under capitalism… From this layer will come some of the best fighters.”9 It’s not necessary to spend time parsing this quote that sits so incongruously in any document in 2022. Suffice to say, actually reviewing where such attitudes derived from with a view to fully correcting mistakes so we can hone and refine our Marxist analysis and programme for today, is absolutely necessary.

Notwithstanding the above, the real experience of Militant in Britain in the 1980s – still an outlier in terms of what Trotskyists achieved in building an organisation of thousands at the cutting edge of a high-pitched class struggle – inevitably was far richer. Working-class women revolutionaries were forged in inspiring working-class struggles with strong socialist feminist elements, including the Militant-led 1983 Lady at Lord John strike in Liverpool against sexual harassment, and the seminal British miners’ strike. Increasingly, women in the regions intervened into the women’s sections of the Labour Party, and began to organise themselves in Militant, including very importantly laying the groundwork for the establishment of a National Women’s Bureau in the earlier part of the decade.

These factors were important precursors to the fact that from the 1990s, a more open approach was taken to socialist feminist initiatives. During the dispute with the IS Majority, the existence of the Campaign Against Domestic Violence (CADV) was held up, not only as an inspiring initiative from the past, but as ‘proof’ that the IS and British NC Majority were beyond reproach on these issues. This way in which it was referenced actually spoke to the opposite – their deficiencies; given that an initiative from a quarter of a century ago was all they could point to, albeit an important one.

There was also a certain dishonesty in how CADV was referenced. The truth is that this initiative emanated not from the IS or British EC – but from women who were mostly outside the central leadership. Certain tensions over a protracted period that existed between the same have been documented by Margaret Creear, former national women’s work coordinator and central organiser of the CADV, in her PHD.10 Details documented in her study speak to many of the strengths of Militant and the Socialist Party regarding socialist feminism, as well as the weaknesses.

CADV – better approach came from outside central leadership

Some of the most striking features of the campaign included the strong written material regarding intimate partner and family-based violence and its development into a significant broad-based campaign with annual conferences and many interventions into trade unions and communities. It also had a positive internal influence in the organisation, including pushing an internal code of conduct to challenge sexism and abuse as it may arise within the organisation, and its work was also the basis upon which the member who was designated as the national women’s organiser was included on the Executive Committee (EC), albeit belatedly and probably reluctantly, according to the memory of some current ISA activists.

As well as the CADV initiative, the CWI took a necessary stance in the 1990s of rejecting so-called ‘post feminism’ – a neo-liberal concept that contended that equality was within the grasp of women if they strove to reach for it as individuals.

As a campaign of the 1990s, the CADV existed in a very different era to today. Any current socialist feminist campaign against gender violence would more easily be able to raise a broader socialist programme. This is because of the mood and consciousness of the working-class and young women who are unwilling to accept any vestige of sexism and oppression; who are already making links organically between different issues, from housing and homelessness, to climate crisis, to systemic racism, to state and interpersonal violence.

One interesting point to note is that in Sweden, the ‘Refuse to be Called a Slut’ campaign was established in the Swedish section in 1998, also at a time of broader retreat of the labour movement, social struggle etc. It had a different orientation to CADV. It was a campaign in the schools against sexism. Like CADV, it was an initiative that broadened into a real and lively campaign that was led by CWI activists, but attracted quite a broad periphery. The key difference with CADV was the fact that it was primarily orientated to very young people, young women in particular – teenagers in high school who wanted to fight against the sexism they experienced there.

In summary, centrally – amongst key figures in the IS over decades – certain weaknesses persisted in relation to a Marxist approach to fighting women’s oppression. This was often not elaborated, but rather was indicated in a lack of political material, a lack of campaigning or internal initiatives, or when important initiatives were developed, for example the CADV, the fact that they were pioneered and pushed from outside the central leadership, with an often luke-warm reception followed by eventual acceptance of the facts on the ground – of good work that had to be recognised.

Gender oppression absent from analysis

Theoretical weaknesses will inevitably affect and limit an organisation’s analysis and points of action in the current. A low point for this was when the draft World Perspectives document for the December 2017 International Executive Committee (IEC) included nothing on gender oppression. This was the year that started with the women’s marches on Trump’s Inauguration Day which marked the single biggest day of protest in US history up to that point, as well as inspiring solidarity protests in cities and towns all around the world. It was the year that ended with the #MeToo social media explosion that reverberated amongst many different social layers across the world, becoming a slogan for workers fighting sexual harassment in their jobs, and is still an iconic reference point today.

This telling omission prompted Swedish delegates to propose a motion to affirm that all our perspectives documents should include analysis in relation to gender- and sexuality-based oppression, consciousness and struggles. Fundamentally, if our perspectives analysis is a guide to action, the real test is to analyse how they fared in preparing us for the feminist awakening and waves of struggle of the 2010s onwards.

While there was some reference in material to the impact of the neoliberal era on working-class women, it was not sufficiently analysed such that points of action for our work were drawn out. In reality, for a period of decades, the roots of today’s radicalisation and struggles have been expanding. These include: increased female participation in capitalism’s workforce, e.g. in the past 30 years there has been a 20% increase in female labour force participation in OECD countries;11 the nature of increased female labour participation in the neoliberal era, e.g. increased women factory workers in the east, increased low-paid service sector workers in the west, where women predominate and the use of less organised, part-time, casual women workers is a means to increase exploitation; the neoliberal attack on already insufficient public amenities, meaning increased exploitation for workers in these sectors where women workers also tend to predominate, entwined with the knock-on negative consequences for women who continue to bear the brunt of unpaid care work; the effects of a certain ideological backlash from the 1990s against gains of previous feminist and labour mass struggles with a proliferation of sexist tropes in mass culture. Furthermore, the political consequences of the Great Recession itself: of increased polarisation, and a turn away from the political establishment, also contains the threat of the growth of the far right, posing a threat to women and oppressed groups but also potentially fuelling further radicalisation of them.

The above gives merely a glimpse into some of the processes happening over decades that have fed into feminist movements and consciousness of the 2010s and 2020s. It’s also important to mention that the increased visibility and activism of the trans community has especially been a feature of the past decade. The brutal reality of capitalism and its inability to deliver basic rights, such as housing and healthcare; its racism that is tied so much with class; its destruction of the environment that threatens human life as we know it; are also all factors driving the material basis for a working-class feminism to emerge.

The CWI failed to sufficiently analyse the above processes and draw out a perspective from the same. We did not predict the scale and depth of the movements and consciousness that have emerged. In fact the minority that split away now, still called the CWI, continued to downplay and understate the movements even as the facts on the ground were already established. They were further impeded in their ability to see what was actually unfolding by their economistic tendency to dismiss the significance of the issue of gender violence. This issue, inextricably linked to the question of the right to bodily autonomy, has been a key theme in the global feminist revolt of the 2010s up to the present day, and will continue to be so. It is an extreme expression of gender inequality and oppression.

Without a sufficient analysis of what processes in capitalism meant for women, and most of all for working-class and poor women’s lives and consciousness, there was inevitably a dearth of conclusions drawn either in terms of mapping out potential flashpoints for struggle, or in terms of concrete initiatives of the CWI linked to these. The success of ROSA in Ireland was a certain inspiration to launch Campaign ROSA in Belgium, an initiative that has made an impression in a growing feminist movement placing a working-class and socialist feminist approach in an influential position vis a vis other trends.

Had an international ROSA – socialist feminist initiative been considered, even in 2016 alongside Campaign Rosa in Belgium, it would have anticipated the openness to anti-capitalist feminism and the strong consciousness for organising on an international basis that has been widespread in the movement, aiding the shaping of its socialist feminist wing, in opposition to liberal feminism.

No longer at the margins

An International Women’s Bureau (IWB) structure was only established with the inception of the ISA. There was never such a structure in the CWI. Sometimes ad hoc meetings of women comrades were convened literally at the margins of international events – during lunch breaks, or at unreasonably late hours after mammoth sessions of the official agenda had finished. This was emblematic of the low priority attached to the socialist feminist work on behalf of the IS members who were setting the agendas.

While members in Brazil were playing a lead role in the PSOL Women’s Sector, a potentially important left plank in the PSOL party as a whole; while US members over the course of a decade were fine-tuning their thoughtful policies to fight sexism inside the socialist movement; while Russian members were testing out more and more socialist feminist initiatives as they were learning that female and gender-queer youth were some of the most open to fight and struggle against Putin – there was no serious, collective drawing out of the lessons on an international basis.

Sexism inside the movement

From very early in the ISA, a conscious approach was taken to the question of waging a struggle internally to foster the most conducive culture possible for the full participation and political development of all members, with special attention given to supporting and assisting those members who suffer different forms of oppression, and with consciously reviewing and rejecting the lack of sufficient attention to the same in the CWI.12

A key part of this is raising the consciousness and understanding of our membership regarding all forms of sexism, harassment and abuse, and to build a zero tolerance approach to these inside our organisations, including codifying this in policies and procedures.

Weaknesses and mistakes made over the years on these questions of course cut across the engagement and development of female, LGBTQ and people of colour members. The struggle to thread socialist feminism and anti-oppression through all our work requires a conscious effort in every regard, including inside all our movements.

Festering behind it all?

A noticeable trend when reviewing weaknesses in the CWI’s history in relation to socialist feminism was the tendency to crudely separate worker and class exploitation from questions of oppression. As well as suffering exploitation and oppression as a member of the working class, the majority of working-class people on a global level will be affected by one or multiple forms of particular oppression, be it racial, gender or sexuality-based oppression, ableism etc. Of course their radicalisation will be affected by all of their experiences of being degraded, hurt and hemmed in by the system of capitalism.

Making a social revolution against the system will involve exploiting every fault line, agitating against every single cruelty and injustice that the system metes out and seeking to build a struggle and movement capable of drawing in the widest possible layers of the exploited and oppressed. Suffice to say the working class, if active, organised and imbued with a socialist consciousness, uniquely has the power to take down capitalism. The unpaid labour of workers is the source of all profits, and by withdrawing their labour workers can shut down the entire profit system. Making a revolution against capitalism will require seizing the key levers of the economy, and naturally workers concentrated in those industries have a strategic role to play, not only in disempowering the capitalist class but also in constructing a workers’ state.

The following quote from the England and Wales Majority in the ‘Name Change Debate’ in 1996 is illustrative of a problem, however:

“…a Marxist organisation [needs] to recognise that it will be a mass movement of the working class, within which the industrial working class will play a key role, which will draw behind it those youth, blacks and Asians, lesbian and gay activists who are presently scattered in single-issue campaigns.”13

Statements such as this are unfortunately guilty of failing to recognise the inter-connection of questions of exploitation and oppression for women workers, workers of colour etc. While purporting to argue the opposite, inherent in the quote is a denigration of struggles on questions of oppression. These are merely ‘single-issue campaigns’. These struggles and these oppressed layers will be ‘drawn behind’ the industrial working class, we’re told. Even the insensitive use of this language is symptomatic of not really trying to win oppressed layers over to socialist and Marxist politics. Sections of society who’ve been systematically told to ‘go to the back’ will not take kindly to any organisation that may display even a hint of such an attitude.

Fundamentally, though, in advocating for the key role of the working class, what’s implied is a view that the most powerful sections of the working class are mainly male, presumably straight, maybe white etc. This was never true, and it’s certainly not true today. The most powerful sections of workers do of course particularly include industrial workers, whose labour contributes so directly to profits for the capitalist class. Millions upon millions of these workers are women, are migrants, are people of colour! Other sectors of the working class are also powerful – retail workers, sanitation workers, transport workers, healthcare workers – the latter not so much because of the direct role their labour has in creating surplus value, but rather because of the role that their labour plays in ensuring the reproduction of a healthy workforce for capitalism. Looking around the world at the working class today only serves to highlight how anachronistic this conservative view of the working class is.

The revolutionary potential

Another unspoken attitude seemed to be a fear that anti-oppression struggles would be divisive within the working class, impeding the working class in building the type of united movement necessary. The opposite is true. Failure to fight sexism, racism, LGBTQ oppression as integral to the working-class and socialist programme would spell a failure to build the type of united class struggle needed. It will also allow liberal feminists to assume leadership positions in movements, derailing these struggles and neutering their potential. Of course, in the midst of working-class struggle, not to mention in the throes of making a social revolution against the whole system, every perceived wisdom and all existing prejudices and ideas will be called into question.

Perhaps the most brilliant and succinct elucidation of a Marxist approach to fighting oppression was given by Irish socialist James Connolly. He was speaking in 1915 about the suffrage movement, and imploring the whole labour movement to get behind it. Extraordinary human that he was, empathy and respect for those suffering oppression exuded from every fibre of his being, and was inextricable from his revolutionary socialism:

“None so fitted to break the chains as they who wear them, none so well equipped to decide what is a fetter. In its march towards freedom, the working class of Ireland must cheer on the efforts of those women who, feeling on their souls and bodies the fetters of the ages, have arisen to strike them off, and cheer all the louder if in its hatred of thraldom and passion for freedom the women’s army forges ahead of the militant army of Labour. But whosoever carries the outworks of the citadel of oppression, the working class alone can raze it to the ground.”14

Notes

- Editorial, 7 Mar 2022, ‘The message from Erdington’, The Socialist, issue 1170, www.socialistparty.org.uk

- Hal Draper, 1976, Women and Class: Towards a Socialist Feminism, p. 7

- Friedrich Engels, 1884, Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, www.marxists.org

- See Kevin B. Anderson, 2016, Marx at the Margins, for further analysis on this question

- Leon Trotsky, 1936, The Revolution Betrayed, www.marxists.org

- C. Arruzza, T. Bhattacharya, and N. Fraser, 2019, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto, Verso

- Colin Wilson, 21 Sept 2014, ‘Dear Love of Comrades: The politics of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners’, www.rs21.org.uk

- George Edwards, ‘Marxism Against Sectarianism’, The Bulletin of Marxist Studies, Summer 1985

- Militant, 1985, ‘Capitalism at an Impasse: Marxists Perspectives for Britain’

- Margaret Creear, 2010, Gender & Class: A Study of Political Activism in North West Labour Women’s Organisation and Militant in the 1980s, Keele University

- Emma Dowling, 2021, The Care Crisis: What Caused it and How can it Be Ended, Verso

- ISA, 27 Sept 2020, ‘France: Victim of Sexual Abuse Speaks Out’, www.internationalsocialist.net

- From the Majority in The Name Change Debate III, 1996, ‘For the Socialist Party Proposal’, www.marxist.net

- James Connolly, 1915, The Re-Conquest of Ireland, www.marxists.org