By Geert Cool, Left Socialist Party (our sister organisation party in Belgium)

War is the continuation of politics by other means. The contradictions of capitalism lead to war. They cannot be negotiated away. Nor do they disappear through further military escalation. Wars usually end in exhaustion, defeat and destruction, or in mass protest that makes their continuation impossible.

It is in the interest of the working class that the war is stopped through mass movements and revolutions, and not through destruction of which the class is the main victim. A revolutionary approach is therefore essential for Marxists. As Trotsky noted in his ‘War and the International’: “War is the method by which capitalism, at the climax of its development, seeks to solve its insoluble contradictions. To this method the proletariat must oppose its own method, the method of the Social Revolution.”

“Capitalism carries war within it, just like clouds carry rain”

As with previous wars, the current one in Ukraine is focused on markets and influence, especially in the era of new cold war and deglobalisation. In ‘War and the International’, Trotsky remarked: “The future development of world economy on the capitalistic basis means a ceaseless struggle for new and ever new fields of capitalist exploitation, which must be obtained from one and the same source, the earth. The economic rivalry under the banner of militarism is accompanied by robbery and destruction which violate the elementary principles of human economy.” The French socialist Jean Jaurès, who was assassinated at the beginning of World War I, summed it up as follows: “Capitalism carries war within it, just like clouds carry rain.”

The horror of war can push the prospect of class struggle for a socialist society into the background. The nationalist wave at the outbreak of World War I engulfed even the numerically strongest workers’ parties at the time. The socialist program, including internationalism, was thrown overboard. Karl Kautsky, the greatest authority in the socialist movement at the time, declared that the international could not be “an effective instrument” in times of war. Whereas previously it had been generally recognised that capitalism led to war and that only the internationally united workers’ movement could stop it, when war broke out socialism was dismissed as the answer. This betrayal was the political end of “the rotting corpse” of the Second International.

Internationalists discuss socialist response to war

The betrayal of almost all the old socialist parties at the outbreak of the First World War came as a shock. The anti-war protest at the outbreak of war disappeared and gave way to confusion, fear and a more visible enthusiastic support for the warring bourgeoisie coupled with hopes for a quick victory. The internationalists were isolated, but took steps to unite.

In 1915, there were the first international anti-war conferences. In March 1915, there was a meeting of 29 socialist women from 8 countries in Berne, at the initiative of the German Marxist Clara Zetkin and the Russian Bolshevik Inessa Armand. Rosa Luxemburg was to attend the meeting, but was arrested at the last minute before her departure. This was followed a few days later by an international youth meeting in Switzerland. At both conferences, the Russian Bolsheviks voted against the final resolution because it was limited to a general call for peace, without defending the need for systemic change and revolutionary struggle against capitalism.

In September 1915, a meeting of 38 socialist delegates from 10 countries and 4 Swiss activists followed in Zimmerwald. After the betrayal of the socialist parties and leaders who all voted for the war credits, there was discussion about responses to the war. Lenin wrote the resolution of the Left at Zimmerwald which concluded: “It is the duty of socialists, while making use of every means of the working class’s legal struggle, to subordinate each and every of those means to this immediate and most important task, develop the workers’ revolutionary consciousness, rally them in the international revolutionary struggle, promote and encourage any revolutionary action, and do everything possible to turn the imperialist war between the peoples into a civil war of the oppressed classes against their oppressors, a war for the expropriation of the class of capitalists, for the conquest of political power by the proletariat, and the realisation of socialism.”

This was opposed by the more right-wing delegates present at the conference who not only opposed calling for a revolutionary solution to war and the need of a full break with the Second International, but even refused an appeal to socialist representatives to oppose the voting of war credits for their national governments. However, the importance of an internationalist anti-war declaration from the workers movement made the left finally agree to a compromise, written by Trotsky, which was a sharp indictment of the war and made the connection between war and capitalism, but did not call for a revolutionary overthrow of the system. Lenin and the Bolsheviks saw in Zimmerwald the embryo of the new International that was needed after the betrayal of the old.

The Russian revolutions of 1917 and the wave of revolutionary movements that followed confirmed the position of the Zimmerwald left.

Revolutions stop the war

It was not through diplomacy that the war ended, but through revolution. On International Women’s Day 1917, textile workers in St. Petersburg kicked off the revolution that overthrew the tsar. With the slogan ‘Land, Bread and Peace’, the Bolsheviks were able to express the main concerns of the working class, the soldiers and the peasants. The October Revolution in 1917 brought about a break with capitalism and opened up a new era in which working people and poor peasants took control of their own destiny. This had an enormous effect on soldiers and workers in all countries across the trenches. The Russian revolution was followed by a wave of uprisings and mass movements. The start of the German Revolution in November 1918 dealt the final blow to the war.

The enthusiasm at the start of the war had given way to dissatisfaction with the shortages, war weariness and the realisation that the war was not in the interests of the working class. The ruling class of all countries feared revolution and anything that suggested a move in that direction, especially mutual solidarity among soldiers on a class basis. That element was present quite soon when it became clear that the war was not a short-lived operation. On Christmas Day 1914, the soldiers came out of the trenches to play football together. The ‘little peace’ in the ‘great war’ showed the solidarity from below against the imperialist clash of arms from above. The army command wasted no time in getting the soldiers back into the trenches to block any further development of that solidarity.

Under these circumstances, it was possible to defend a socialist anti-war position even from an isolated position. This meant first and foremost a call for collective resistance, as Karl Liebknecht heroically did on 1 May 1916 when, dressed in his soldier’s uniform, together with Rosa Luxemburg and other supporters, he shouted with a red flag in his hand: ‘Down with the government, down with the war’. The trial of Liebknecht would lead to the first strikes. After violence against a solidarity demonstration on 27 June 1916, the day the verdict in the first instance was pronounced, 55,000 workers in the munitions industry went on strike one day later.

This approach of calling the soldiers and the working class to battle was essential. It was much more efficient than the method of individual terrorism propagated by the Austrian socialist Friedrich Adler. Out of aversion to the treachery of the Socialist Party, co-led by his own father Victor Adler, Friedrich Adler decided to take what he considered radical action. In October 1916 he shot Prime Minister Stürgkh. Like Liebknecht, it earned him a heavy prison sentence, but Liebknecht’s approach provided the impetus for a nascent anti-war movement. Trotsky remarked: “Friedrich Adler is a sceptic from head to foot: he does not believe in the masses, or in their capacity for action. At the time when Karl Liebknecht, in the hour of supreme triumph of German militarism, went out to the Potsdamerplatz to call the oppressed masses to the open struggle, Friedrich Adler went into a bourgeois restaurant to assassinate there the Austrian Premier. By his solitary shot, Friedrich Adler vainly attempted to put an end to his own scepticism.”

The key to change lies in trust in the masses and their capacity for action. This was the guiding principle of revolutionary Marxists throughout the First World War. During the war, Lenin repeated it again and again: only a workers’ revolution can end the war. What seemed utopian to many in 1914 became reality in 1917–18. The war again became the midwife of the revolution. In Russia, it was successful because there was a well organised revolutionary party with a Marxist program and rooted in the class. That revolutionary party did not choose the historical conditions in which it was active, but it did seize every opportunity and possibility that presented itself.

Mass movements today

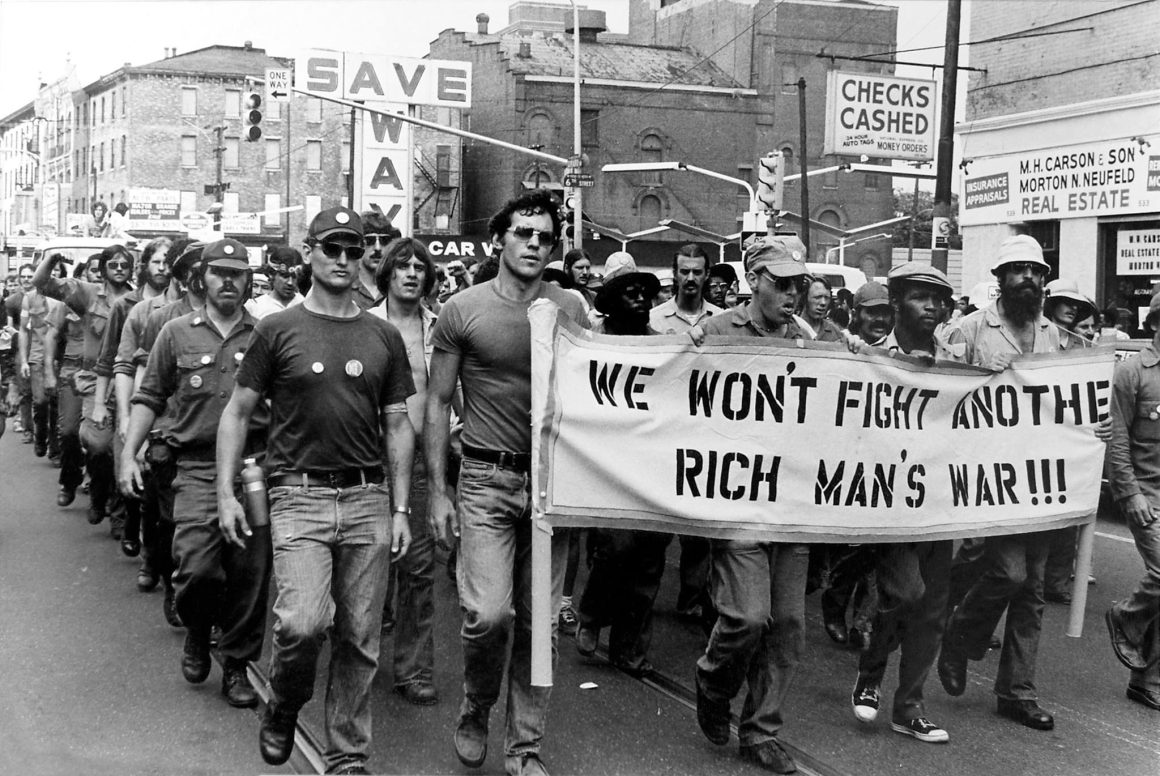

Sceptical readers will think: yes, but that was more than a century ago. Today, warfare looks completely different and the circumstances are less favourable. To begin with, there are more recent examples of mass movements that have stopped wars. In 1973, US President Richard Nixon saw no other option than to withdraw troops from Vietnam. Continuing the war threatened sparking an uncontrollable social revolt in the US itself.

That mass protest needs a political alternative is a lesson from many movements. Lack of clarity about an alternative to the status quo is a weakness that is ruthlessly played upon by dictators and warmongering ‘leaders’. That was the main reason why the counter-revolution in Tunisia and Egypt could return to the fore after the revolutionary wave in North Africa and the Middle East in 2011. It was also the reason why the massive anti-war movement of 2003 with millions of demonstrators around the world could not ultimately stop the invasion of Iraq. Without broad-based support for systemic change — recognising capitalism itself as the cause of wars and defending socialism as an alternative — no decisive step was taken in 2003 towards strikes and industrial action to shut down the ports, the arms industry and every move towards war. We did everything we could to strengthen that anti-war movement and popularise workers’ action proposals, including taking initiatives ourselves for school and student strikes on Day X, the day the war began. The protest against the war in Iraq showed that a mass movement is not enough, there is a need for a Marxist program and accompanying revolutionary approach.

Socialists today still do not create the historical stage on which we operate, but must act on the ground that history has laid before us. This means that we should not wait or watch as commentators from the sidelines. Every opportunity to strengthen the resistance of the working class to war and barbarism must be seized. As Trotsky said: “The war does not solve the labour question on an imperialistic basis, but, on the contrary, it intensifies it, putting this alternative to the capitalist world: permanent war or revolution.”

The war propaganda will undoubtedly have an effect, yet the internationalists today are not as isolated as during WW1. There is little enthusiasm for this war, and that’s even before its hopelessness and its toll on the working class are widely visible. After the failure in dealing with the pandemic, the capitalist leaders are now demonstrating their inability to offer humanity a better future. It is their approach and politics that are being blown to pieces by the cannons. Marxists are hopeful: we have to use the failure of the old system to establish enthusiasm for a new one. Our program in the anti-war protests is still that of the Zimmerwald left: to stop the war by a revolutionary mass movement against the capitalist system that produces war.